A newly announced “Crypto Climate Accord” aims to erase cryptocurrencies’ legacy of climate pollution. That’s a tall order considering the enormous amounts of energy that the most popular cryptocurrencies — bitcoin and Ethereum — consume. The loose goals laid out in the plan so far face potentially insurmountable challenges.

The “accord” is led by the private sector — not governments — and outlines a few preliminary objectives. It seeks to transition all blockchains to renewable energy by 2030 or sooner. It sets a 2040 target for the crypto industry to reach “net zero” emissions, which would involve reducing pollution and turning to strategies that might be able to suck the industry’s historical carbon dioxide emissions out of the atmosphere.

Lastly and perhaps most realistically, it aims to develop an open-source accounting standard that can be used to consistently measure emissions generated by the crypto industry. They also want to develop software that can verify how much renewable energy a blockchain uses.

If achieved, those goals would solve a very real problem. Bitcoin alone has roughly the same carbon footprint annually as Hong Kong, while Ethereum’s annual carbon emissions rival Lithuania’s. Their climate pollution is growing even as scientists’ research warns that global emissions need to be cut almost in half this decade to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

The accord has support from some influential names in climate action and the crypto industry — including cryptocurrency company Ripple, blockchain technology conglomerate Consensys, billionaire climate crusader Tom Steyer, and the United Nations-appointed “climate champions.”

While tackling the environmental damage done by the crypto industry might be a worthy challenge, critics say the broad goals are unlikely to result in meaningful change.

“Some things just can’t be fixed,” says economist Alex de Vries.

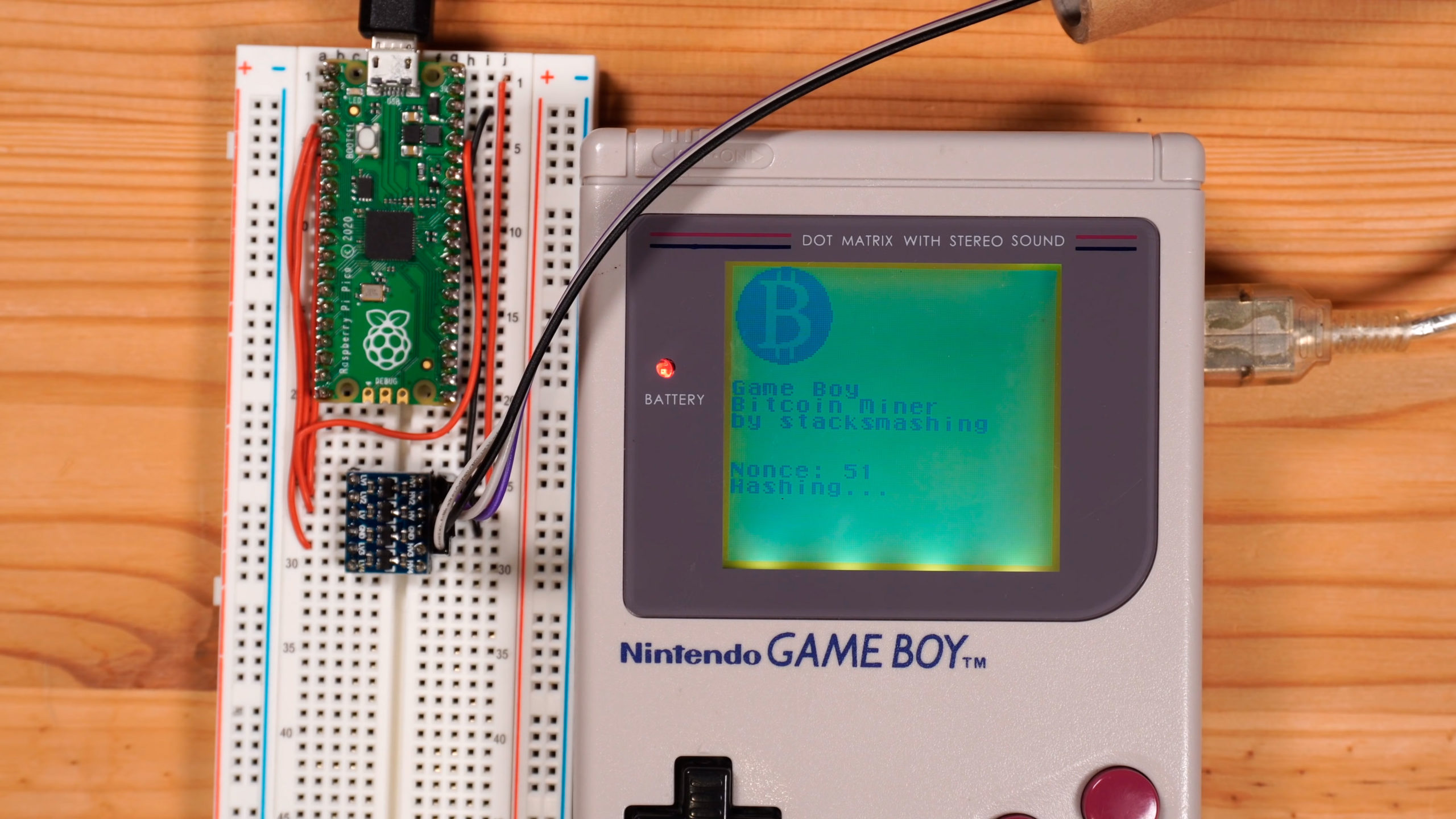

Unfortunately for the Crypto Climate Accord, bitcoin is the biggest player in the game, and it’s likely to cause the accord the most trouble because of how much energy it uses. Bitcoin is purposely inefficient — which is a problem renewables can’t fix. It uses a model called “proof of work” to keep its ledgers secure. “Miners” who verify transactions to get new coins do so by using energy-guzzling machines to solve increasingly difficult puzzles. (Ethereum also uses proof of work but has said for years that it will eventually transition to another model.)

Those machines will continue to compete for renewable energy with arguably more essential needs, like keeping the power on in people’s homes. And if cryptocurrencies increase electricity demand beyond available renewable resources, utilities might turn to fossil fuels. That’s why cleaning up energy sources and increasing energy efficiency are two sides of the same coin when it comes to tackling climate change.

Regardless, the accord’s founders are optimistic about a greener future for bitcoin. “I’ve been in conversation with folks from the bitcoin ecosystem, it’s a pretty simple pitch,” says Jesse Morris, chief commercial officer of the nonprofit Energy Web Foundation, which is spearheading the initiative. “If we can make bitcoin green, it will be much easier and lower risk for other organizations to come in and buy more Bitcoin.”

Bitcoin still accounts for more than half of the entire cryptocurrency market capitalization. But it is facing competition from newer cryptocurrencies that have found ways to be greener. Other cryptocurrencies use different blockchain technology than bitcoin and consume very little energy in comparison as a result. For those cryptocurrencies, like Ripple’s XRP, running on renewables could be more feasible.

And while renewable energy costs have fallen dramatically, luring bitcoin miners to places with abundant renewable energy would likely require heavy subsidies to keep them from turning to cheaper, dirtier fuel sources, de Vries says. “Just the sound of that — It sounds really wrong,” he says. “Why would you want to subsidize an industry that uses energy just because it is set up to waste resources?”

The new crypto accord, however, is “not about coming together and asking for subsidy by any means,” says Morris. “We just want to get everybody together and start nailing the action here.” Many blockchains, like bitcoin, were designed to be a decentralized system with no top-down oversight. So getting everyone on board, even within a single blockchain, will be a huge task.

The accord’s objectives are supposed to be fleshed out and finalized by the time a big United Nations climate conference rolls around in November. But Morris admits that the initial plans chase big aspirations rather than fine details. “So many of these other decarbonization efforts are very much thinking their way into acting,” Morris says. “Whereas in Crypto, because it’s kind of the Wild West, it’s about acting our way into new thinking.”