Streaming services are slowly turning into cable TV — complete with bundles, an ever-growing list of channels, and a reinvented TV guide. And a series of lawsuits could portend the return of something even worse: the hidden cable fee.

Three municipalities in Georgia are suing Netflix, Hulu, and other streaming video providers for as much as 5 percent of their gross revenue in the district — joining a nationwide group of towns and counties that want these services regulated more like cable TV. It’s a small but growing front in the war over cord-cutting, challenging regulators to decide which matters more: the increasing role streaming services play in American media diets or their significant practical differences from traditional TV.

The federal lawsuit, reported earlier this month by Atlanta Business Chronicle, was originally filed in state court last year. It argues that Netflix and Hulu — along with satellite providers Dish Network and DirecTV, as well as Disney’s entertainment distribution division — violated a 2007 law called the Georgia Consumer Choice for Television Act. That rule specifies that “video services” must pay a quarterly franchise fee to local governments, unless they’re part of a larger internet service package or operate wirelessly.

Georgia isn’t the only place where local towns are pushing for streaming fees. As The Hollywood Reporter reported last year, two law firms recently filed similar suits on behalf of towns in Texas, Indiana, Ohio, and Nevada. And in 2018, the city of Creve Coeur, Missouri paved the way by suing Netflix and Hulu under that state’s franchise laws. With municipal budgets cratered by the pandemic, slapping a franchise fee on cash-heavy tech companies has never been more appealing.

A single successful lawsuit could cost these companies millions. Gwinnett County, one of three municipalities named in the suit, charges 5 percent of a company’s local gross revenue in franchising fees. A filing calculates that Netflix made $103 million from Gwinnett County subscribers over the past five years — which would translate to $5.15 million in retroactive fees for that area alone. (Netflix declined to comment on the numbers cited in the story.) The plaintiffs in these cases are seeking class action status, which would make companies liable for any “similarly situated” state locales as well.

TV providers have opted to directly bill subscribers for franchise fees, and companies like Netflix and Hulu could follow their lead, passing the costs to users. Those fees aren’t why cable costs so much, and they help fund important services — but they’re also something many consumers find irritating or bewildering.

If the cases succeed and aren’t preempted by any federal laws, they could draw streaming services — a category that’s exploded in popularity — under a new regulatory umbrella. Even traditional TV providers have moved to online streaming: the suit notes that Dish and DirecTV chose to “fundamentally change” their satellite-only options by adding services like the Dish-owned Sling TV, which routes live TV over broadband networks.

The Georgia suit in particular could have broader, potentially unpredictable effects. Its definition seems to potentially encompass many smaller and less profitable streaming video companies, although there’s far less incentive to sue them. Meanwhile, the exemption for internet service packages could give telecom-run streaming offerings — like Comcast-owned NBCUniversal’s Peacock service — a built-in advantage over competitors like Netflix.

The Consumer Choice for Television Act wasn’t passed with streaming video in mind. Passed in 2007, the law amended existing rules meant for cable TV providers, which pay franchise fees for the right of way to lay wires along public infrastructure like roads. “It’s a remnant of how we did cable franchising,” says John Bergmayer, legal director of the internet-focused nonprofit Public Knowledge. And it specifically exempts some services that don’t require that physical access, like programming from mobile services.

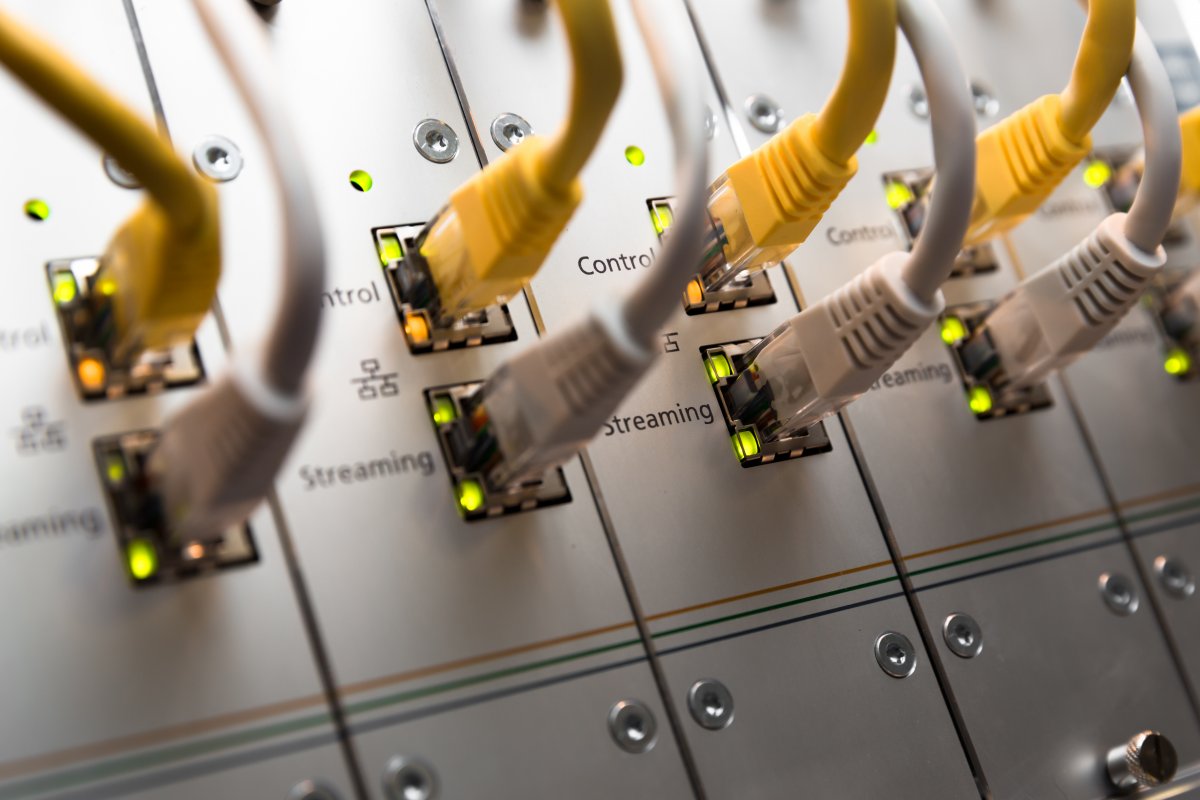

Despite this, the municipalities contend that streaming companies tick the same legal boxes as cable TV. The complaint says people are getting a similar service; in the complaint’s words, they “view professionally produced and copyrighted television shows, movies, documentaries, and other programming.” More technically, it argues that this programming counts as a “video service” because it’s carried over public internet lines that require the right of way.

But conversely, the suit also notes that streaming giants like Netflix aren’t just running over a global internet backbone. They’re building local content delivery networks (or CDNs), like Netflix’s Open Connect, which route user traffic to a nearby server. Internet service providers in many states — including Georgia — already pay for broadband rights of way, and the servers are located in data centers, not underground pipes or utility poles on public land.

The companies have objected to the string of franchise fee lawsuits. “These cases falsely seek to treat streaming services as if they were cable and internet access providers, which they aren’t,” a Netflix spokesperson told The Verge. “They also threaten to place a tax on consumers that the legislature never intended, and we are confident that the courts will conclude that these cases are meritless.”

Franchise fee claims — all based on different local laws — remain mostly untested in court. But earlier this month, a Missouri state judge rejected an early bid to toss that state’s lawsuit, agreeing with the claim that these companies were “video service providers.” The judge specifically noted the presence of CDNs like Open Connect, a system that “bypasses the ‘public internet’” and distinguishes streaming giants from smaller services. She also rejected claims that the federal Internet Tax Freedom Act provided blanket protection from the fees.

With little precedent, it may take years to understand the implications of these cases. Companies will likely appeal any decision, and unless the Supreme Court takes up one of the cases, states will be covered under a patchwork of lower court rulings. But an increasing number of local governments see these fees as an opportunity to recover money from the services that are slowly replacing cable TV. “They need money now, and they’ve got this law on the books,” says Bergmayer. With the status of streaming services in flux, they’ve settled on an optimistic approach: “let’s go for it and see what happens.”