It was March 2020, and restaurants across the country were shutting down, setting up takeout windows, or doing whatever they could to absorb the shock of COVID. But it was Chuck E. Cheese, of all places, that had the foresight and steely clarity to see not just what the new era required, but what it permitted. With much of America suddenly interacting with restaurants through delivery apps, the food industry had been transformed into e-commerce, and the arcade better known for its ball pits than its food was free to invent a new identity: “Pasqually’s Pizza & Wings.”

Pasqually’s cover was blown a month later, when Kendall Neff of Philadelphia wrote on Reddit that the pizza she ordered from what she believed was a local mom and pop in fact came from Chuck E. Cheese operating under an alias. But the gambit was a success. This March, the company told the trade publication Food on Demand that Pasqually’s is here to stay. And it is far from alone. In fact, during a period when restaurants closed en masse, restaurant brands proliferated.

Big chains like Denny’s and Red Robin spawned brands like The Burger Den and The Wing Dept., both announced earlier this year. Meanwhile, a new group of companies is aggressively courting restaurant owners and enlisting them to run delivery-only brands out of their existing businesses. Restaurants can choose from a menu of brands with names like Hot Dog Station, Salad Box, Mr. Cheeseburger, or Grilled Cheese Society.

These are called virtual brands, and as with so many pandemic trends, they preceded COVID but were accelerated by it. In the past, restaurants might occasionally use aliases to increase their likelihood of appearing in search results, and Uber Eats has had a program helping restaurants set them up since 2017. But when it came to imagining the future of delivery, most attention and funding focused on the virtual brand’s better-known cousin, the ghost kitchen. Startups like Uber co-founder Travis Kalanick’s CloudKitchens garnered large investments on the premise that multiple delivery-only restaurants sharing specialized commissary spaces would be efficient enough to thrive in the low-margin world of food delivery.

Virtual brands in some ways represented an opposite bet: that there are already too many restaurants, with too much kitchen capacity sitting idle, and that it can be put to use running delivery-only brands. Then came COVID, and every restaurant abruptly had extra kitchen capacity and a desperate need for revenue. There followed a Cambrian explosion of virtual brands. Uber Eats estimates the number of virtual brands on its platform more than tripled in 2020, to over 10,000. Grubhub reports a similar boom. According to a report the company released this year, 15 percent of restaurants operated a virtual brand before the pandemic. By the end of 2020, 51 percent had at least one.

And many have more than one brand. A lot more.

“Now in my little, 1,000-square-foot restaurant, I’m now carrying about 12, 14 brands,” says Ty Brown, with some astonishment.

It started gradually. Brown, a 43-year-old entrepreneur living in Brooklyn, had just opened The Bergen, a small takeout spot in his neighborhood, when he got a call from someone in California who said he was with a company called Future Foods. (Future Foods is actually an arm of Kalanick’s notoriously secretive ghost kitchen company, as food journalist Matt Newberg reported in June, though the two do not publicize their connection.) The pitch was simple: Brown was already making burgers and wings at The Bergen, so Future Foods would set him up with some additional brands — Burger Mansion and Killer Wings — which the company would list on delivery apps. Whenever someone bought from one of these brands, Brown would fill the orders, and Future Foods would send him a check for the revenue, minus its cut of around 20 percent.

The Bergen was Brown’s first restaurant, though far from his first business. He’d long been active in his neighborhood through a variety of ventures, chiefly the Brooklyn United Music & Arts Program, a nonprofit youth center and marching band he founded and runs. The kids in the program were always asking their parents about dinner, he says, so when he noticed the restaurant down the street had closed, he decided to lease it and open a spot of his own. Future Foods seemed like a helpful boost as he got on his feet.

He also hoped it would give him an edge on the apps that dominate delivery. Like many restaurant owners, his relationship with the apps is one of fraught dependence. He relies on them for orders and to handle delivery, but their fees, plus the advertising he says he must buy in order to get noticed, means he ends up paying them up to 25 percent of his revenue. “It’s pay to play,” he says.

In their pitches to restaurant owners, virtual brand companies offer to change this dynamic. Some claim to be able to get better rates with the app companies because they negotiate representing hundreds of restaurants rather than just one. They handle advertising and buy it at scale. Often, sales reps hint at arcane knowledge of platform algorithms. (One restaurant owner had been advised to open on a certain day and keep certain hours to win the algorithm’s favor.) But at the simplest level, they supply the menus, photos, and brand names: Something Fishy Fish and Chips, Hey Burger, Tendies Chicken Tenders.

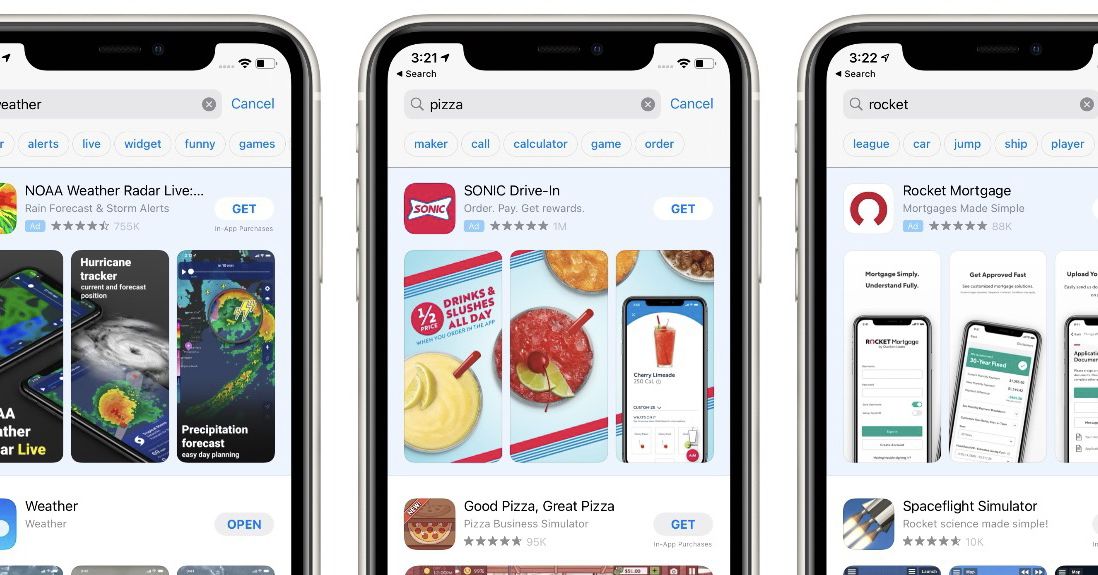

“With the virtual brands thus far, a lot of it really boils down to search optimization,” says Melissa Wilson, a principal at the food service consulting company Technomic. Just as the incentives and constraints of Google search or Facebook’s News Feed gave rise to certain emergent styles — the keyword-crammed headline, the clickbait tease — digital brands are converging on a distinctive form. Because people search for food on delivery apps in much the same way they search for anything else online — by product type rather than brand — specific restaurant names like The Bergen, named after the street it’s on, or even Denny’s and Red Robin, are too opaque.

(In retrospect, even Chuck E. Cheese’s Pasqually’s feels like a transitional stage on the way to a fully optimized future, one that hasn’t lost its vestigial human name. Insisting it never meant to deceive, the company has pointed out that Pasqually is actually the name of the chef who took in Chuck — or rather, Charles Entertainment Cheese — the orphaned mouse who, according to the character’s surprisingly developed and unexpectedly tragic backstory, throws birthday parties for children to make up for those he never had. “If you’re a brand fan of Chuck E. Cheese, you know who Pasqually is,” an executive assured the trade publication QSR. “They’re curious to know what Pasqually’s might taste like.”)

The newer virtual brands are, paradoxically, distinctively generic. They share an uncanny familiarity, like the name of a restaurant in an airport food court — something that you feel like you’ve heard of before but can’t quite place: Noodle House, Pasta Mania, Chef Burger. It doesn’t take long to develop an ear for them. Technomic’s Wilson picked out two near her: Craftsman Bowls and Craftsman Burgers, spinoffs of a local steakhouse. I first contacted Brown after scanning Grubhub and spotting Wing Dynasty, a name that is both suspiciously bland and contains the truest tell of all: wings.

“Oh my god, I’m so sick of talking about chicken wings!” exclaims Food on Demand’s editor Tom Kaiser, laughing in a way that makes clear he is actually not. “How many wings are people eating in a given week? It’s crazy.”

If virtual brands are the response of an industry transformed abruptly into e-commerce, wings are the iPhone charger, the weighted blanket, the product that is profitable, in-demand, and so close to being a pure commodity that just about everyone is trying for a piece of the action. Just as hundreds of brands with arbitrary names like ASLTW and GOSICUKA will pop up on Amazon to sell identical cables or hair ties made in the same factory, because no one brand dominates and anyone has a shot at winning the algorithmic lottery, wing brands exploded over the last year.

Rishi Nigam, CEO of Franklin Junction, calls it “the great chicken wing rush of 2020.” His company mostly matches established brands with restaurants that have excess capacity — in practice, often chains inside chains, like the Canadian seafood company The Captain’s Boil, which ran for a time out of Ruby Tuesday — but it made an exception for wings, launching Wings of New York, a virtual brand from the hotdog company Nathan’s Famous, as well as WingDepo, which runs out of Frisch’s Big Boy. (With virtual brands, it all gets very complicated very quickly.)

From April 2020 through February 2021, a period when restaurant visits and orders dropped by about 11 percent, wing sales actually rose by 10 percent, according to David Portalatin, senior vice president food industry advisor at NPD. “American restaurants in the United States have served more than a billion servings of wings since the pandemic came along,” Portalatin says. The same period saw wing prices surge far beyond their pre-pandemic level. According to USDA data, wing prices in the Northeast were up nearly 50 percent at the end of February 2021 from where they were the year before, and they have continued to climb. There have been warnings of wing shortages.

Wings, like pizza and unlike, say, tacos, handle delivery well, and some of the restaurants that specialize in wings, like Wingstop, were already adept at digital ordering and particularly well-suited for the pandemic, Kaiser says. Wings are also extremely simple to make. “It’s a one-ingredient menu, right?” says Nigam. “There’s no barrier to entry. You and I could launch a wing brand by 6PM tonight.” Crucially, no one brand dominated the category, and there is no proprietary wing type or sauce, so any given restaurant’s overnight wing brand had a decent chance of winning attention on the delivery apps. This made wings an obvious first target for restaurants that had idle kitchens and needed additional revenue.

“It all added up to a perfect storm,” says Portalatin, “for wings.”

Spencer Rubin, founder and CEO of the New York sandwich chain Melt Shop, had been thinking about testing a wing brand before the pandemic, maybe for football season. Then COVID hit and his walk-in business evaporated. People were ordering dinner more than lunch, Rubin observed, and were particularly interested in “craveable” comfort foods, and there were only a few good wing brands in New York City, so he launched Wing Shop. “We got lucky with that one,” he says, being among the early entrants to the great wings rush. Now “everyone and their mother is launching a wing concept.”

Big chains like Applebee’s jumped in, first with the brand Neighborhood Wings, then with Cosmic Wings, an attempt to establish a proprietary moat through exclusive Cheetos dust. Chili’s launched It’s just Wings. The Smokey Bones barbecue chain launched The Wing Experience.

Meanwhile, virtual franchises started hitting up independent operators and pushing them to take on additional wing brands.

“It was crazy with wings,” says Dawn Skeete, the owner of Jam’it Bistro. She opened her Jamaican restaurant in south Brooklyn in 2019, and when the pandemic hit, Future Foods seemed like an appealing way to test what items at what prices sold in her neighborhood. The barbecue brand, OMG BBQ LOL, didn’t work out, but she kept going with Just Wing It. Then she took on a second wing brand, Wing Spot, after a new virtual franchise company called Acelerate.io approached her.

Acelerate.io is an LA-based company founded by a former DoorDash employee named George Jacobs, who felt that for delivery to be profitable, kitchens had to increase “throughput” by operating multiple restaurants. The company launched in late 2019 — with a wing brand, naturally — and now runs seven brands in “several hundred” restaurants across the US. (It’s spelled “Acelerate” because it’s “more efficient with just one c,” Jacobs says, but also because “accelerate.com” was too expensive.)

Just Wing It and Wing Spot have the same menu, Skeete says, which helped with bulk purchases as wings got more expensive. “Wing prices are going through the roof, and I think it has to do with all these virtual kitchens that are doing wings,” she says. She’s now looking to take on a third wing brand.

Brown always made wings at The Bergen, both under his own name and Future Foods’ Killer Wings. Business was good for much of 2020. The Bergen’s takeout and delivery-focused business was well-positioned for the spring lockdowns. It got publicity for donating meals to families in need, followed by more attention as a local Black-owned establishment during the protests surrounding George Floyd’s murder. The pace was almost more than staff could handle.

But by the end of the year, business was flagging, so in January, Brown responded to a pitch from Nextbite, an arm of the restaurant software company Ordermark. The company recently received a $120 million investment from SoftBank and has been expanding aggressively, offering restaurant owners, which it calls “fulfillment partners,” a selection of “turnkey” virtual brands from which to choose.

“Nextbite, man, the day I opened up that brand, they put out a lot of wings,” says Brown. “I had to go shop for more wings. I had to go open up a credit account in order to just carry enough wings. I had to go buy more freezers.”

The new brands were doing better on the apps than The Bergen, a fact Brown attributes to their ability to game their algorithms. “I call it the wizard behind the curtain,” he says. If a brand’s sales are low, he’ll call his support person at its parent company and ask them what’s going on. “Can the wizard click the magic button?” he jokes. “They start laughing at me, but they tell me that they know the algorithm, they know how to make sure we’re first on these websites.” A few days later, the orders flood in.

It worked so well he signed up for another company, The Local Culinary, a Miami-based business that started as a ghost kitchen but pivoted to the virtual franchise model last year. Next came Virtual Dining Concepts, that one run by Robert Earl, the former CEO of Hard Rock Cafe and Planet Hollywood. Earl launched Virtual Dining Concepts in 2019 after becoming disillusioned with the economics of ghost kitchens. It started, as all things do, with a wing brand, Wing Squad, being run out of Buca di Beppos and other restaurants he owns. But during the pandemic, he began licensing brands to other restaurants as well as coupling them with celebrities, an attempt to bring the power of fame and virality to the search-dominated delivery sector. Recent innovations include Tyga Bites and MrBeast Burger, which Earl says will be operating out of over 1,000 kitchens by the second half of this year.

Brown found it to be a polished operation: video modules to train staff on how to prepare the food and a requirement that they send in a photo of it packaged with branded stickers.

Soon, he was selling burgers under the names of Chef Burger, Burger Mansion, Hey Burger, and MrBeast Burger. Wings were sold under the names CHICKS, Wild Wild Wings, Crispy Wings, Killer Wings, Firebelly Wings, and The Wing Dynasty. It is a mathematically daunting array of burgers and wings, and that is to say nothing of newer additions like Hot Dog Station and Hot Potato.

Yelp reviews for The Bergen show complaints over late and mixed-up orders, including several in which orders are confused for other brands. “So I ordered from a restaurant called Hook, Line and Seafood, and some time later I received a call from The Bergen,” reads one of several one-star reviews. “Evidently they’re at the same address.” Brown has begun offering raises to employees who can memorize all the menus.

Yet, from another perspective, it is all very simple: burgers, chicken sandwiches, wings. “They’re branded differently but they’re made the same,” Brown says. “A cheeseburger with egg and bacon is called a Morning Glory. Somebody else calls it a breakfast sandwich. Somebody else calls it the Egg-o-nomitor — I don’t know, I’m making it up, but it’s the same exact thing, it just depends on who’s calling it what.”

“Instead of saying buffalo wings, they might say classic wings,” he goes on. “It’s the same exact wing, man. One might have one sauce different. My wings, their wings, the other wings — they’re all the same wings. I even stopped making my wings the way I used to make them. I’m a Black guy. We used to season our wings. I stopped because nobody else is doing it.”

Other elements of The Bergen’s menu have begun to resemble its corporate guests. If a brand has a burger that’s selling well, Brown will add it to his own menu — he’s already buying the same ingredients, after all — under yet another name.

Proponents of digital brands and ghost kitchens often pitch them as a way for chefs to experiment. When you don’t have to lease new space or hire new staff, it becomes less costly to try something new. At the same time, the availability of data about what works, platforms that algorithmically reward success with more success, and the way people search for generic products all create evolutionary pressure in the same direction. It’s a push-pull we’ve seen play out on other platforms. In theory, people are free to try weird things; in practice, most everyone makes wings.

Other restaurant owners are warier of the trend. Robert Guarino, who owns several restaurants in New York and is the CEO of Five Napkin Burger, started a virtual brand last summer (wings, of course) but is winding it down now. He warns that grafting delivery brands onto an existing restaurant can be harder than the pitches make it out to be. Capitalizing on excess kitchen capacity seems simple until owners realize everyone is ordering from all their menus between 6 and 8PM, or that multiple items need the same equipment, or that staff can’t keep up. “Restaurants are in some ways little factories; in some ways, they’re not,” he says.

His other concern is longer term, and one shared by many in the industry: that the delivery apps themselves will launch virtual brands. They have the data on what foods perform well, and they control what restaurants rank highly in search; what’s to stop them from launching a virtual brand themselves, asks Guarino, or offering brands to restaurants willing to pay them higher fees? “That’s the moment that the independent restaurant community has always been afraid of,” he says.

Andrew Rigie, executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, compares it to Amazon’s practice of using data gleaned from its Marketplace to identify successful products and sell its own version. “It’s kind of the next logical step,” says Rigie. “It’s like Amazon Basics, where they say, ‘Okay, we’ll continue to sell your burgers, but now we’ve learned how to make our own burgers, and if you want your burgers to be listed above our burgers, you’re going to have to pay an additional premium.”

It’s not an unreasonable fear. None of the delivery apps have managed to make the business consistently profitable, and while margins in the restaurant industry are thin, it represents at least a possible path to financial viability. The apps are also facing the threat of defections over their high fees, as some restaurants start handling orders and delivery themselves. Running virtual restaurants would be one way to maintain a baseline selection on the platform.

The apps and the franchises are already working closely together. In December, Grubhub launched a program called Branded Virtual Restaurants, a partnership with Virtual Dining Concepts and the Chicago restaurant group Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises, and began running Facebook ads and sending emails courting owners. “These are simple, low-risk solutions for adding a new revenue stream to your business without increasing your overhead costs,” reads one Grubhub email inviting restaurant owners to sign up for brands like Pauly D’s Italian Subs or Mario’s Tortas Lopez. “Each Branded Virtual Restaurant is backed by a celebrity and national marketing campaign that’s sure to attract new customers to your restaurant.”

Brown received the pitch and is enthusiastic about the partnership for the same reason other restaurant owners are wary: he believes Grubhub’s involvement will give him an advantage. Searching for ways to open more brands, he recently expanded into a second Brooklyn location and is setting up outposts in Orlando and Atlanta. He hopes to open each with 15 to 20 brands. He feels the virtual restaurant boom is just beginning. He’s getting more and more ads and inquiries inviting him to sign up with brand after brand.

Recently, he learned about yet another company joining the rush. Google is testing a partnership with Nextbite and will be placing orders using its delivery service from Brown’s shop, among others. (Nextbite said it had no information to share at this time. Google did not respond to a request for comment.) It’s an ominous sign for the delivery apps which, after inserting themselves between customers and restaurants, now face the prospect of a yet bigger company doing the same to them. But for Brown, it’s a vote of confidence from one of the largest companies in the world that the future he’s betting on is the right one.

It’s a strange future, one where restaurants find a way to thrive in the low-margin world of delivery by becoming something else, something more like a food factory optimized for maximum output, with its production lines determined by an assortment of technology platforms and branding companies. It’s a more opaque world than the industry seemed to be headed toward a few years ago, when restaurants were advertising locally sourced ingredients and gesturing toward transparency in their supply chains. Instead, it will have some of the mystery of e-commerce, where a single click summons an item — from where exactly is unclear, and less important than the speed with which it arrives. In exchange for the specificity of physical restaurants, consumers will have an abundance of ever-changing choices, though perhaps all made in the same kitchen, and will find whatever it is they search for, especially if it’s wings.